I’m skipping twenty or so books I’ve failed to write about in a timely manner in favor of some more recent ones.

I love London, history, underground things, and spooky things–therefore this was a pleasure to read. It’s not a linear history or narrative, more a series of vignettes focusing on different underground aspects of London (sewers, wells, lost rivers, Roman ruins, the Underground itself). I could fault it for its glancing and non-specific references to things I then had to look up elsewhere (like the Roman bath-house in the basement of a Thames-side office building) but I enjoyed the looking up as well. The next time I visit London I’ll try to find some of the hidden sights–the Clerk’s well at Clerkenwell, the spots where you can hear the underground rivers flowing, and the section of Roman wall in the middle of a car park.

The preschool my kids attend has a fundraising auction every year. This year one of the things up for auction was a large set of Russian books (in translation) along with a bottle of vodka. I’d only read two of the set before and was unable to resist bidding. So … now I’m committed to reading all of them. Easing my way in, I started with an early and short Tolstoy novel, The Cossacks.

It’s a little odd to be reading it when Cossacks are actually in the news, but it’s a fine romance–more romantic toward the place and the people Tolstoy and his wealthy Moscow hero encounter than a woman, though there is a woman. Read it when you’re in the woods.

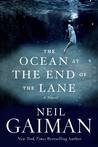

The Ocean at The End of the Lane – Neil Gaiman

The Ocean at The End of the Lane – Neil Gaiman

Short, sweet, creepy, and a little brutal. All very history / memory / loss / childhood (and creepy things) and so very like The Graveyard Book or Coraline, except for adults.

God’s Jury: The Inquisition and the Making of the Modern World – Cullen Murphy

God’s Jury: The Inquisition and the Making of the Modern World – Cullen Murphy

Quick summary: The Inquisition–Cullen Murphy’s not a fan. It’s a very opinionated history. On the other hand, the various Inquisitions were pretty nasty, and don’t have a lot of defenders. Murphy does a nice job of laying out the different Inquisitions that have existed and their interrelationships (something I was totally unclear on before reading this).

Song of the Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths – Nancy Marie Brown

Two books in one. One is a history of Snorri Struluson, author of the Prose Edda and ultimate source for a large majority of everything we know about Norse legend. Sadly, I found this (the majority of the book) pretty dry, even as I understood it shouldn’t be–Snorri is a central figure in Icelandic history even apart from the Edda. It shouldn’t have been dull, but it was. The other part of the books talks about the process through which the sagas (Snorri’s and others) found their way into other histories, art, literature, right on up to Wagner, Tolkien, and the Marvel Comics version of Thor. That part was well done and fascinating.

I do love that 700+ years after he dies you can go visit his hot tub, though.

Also read:

A Crown of Renewal by Elizabeth Moon

Satisfying final chapter of a fantasy series that dragged on a bit long.