We do it dozens of times a day, every day, but why do we call it logging in?

“Log in” is one of those phrases that sounds weirder the more you say it. It’s ubiquitous in online life, though it does seem like it’s being slowly overtaken by “sign in” [note 1]. But where does the phrase come from in the first place?

Clearly, a job for the Oxford English Dictionary. Luckily you can usually access the online OED through your local public library site. Thanks, libraries!

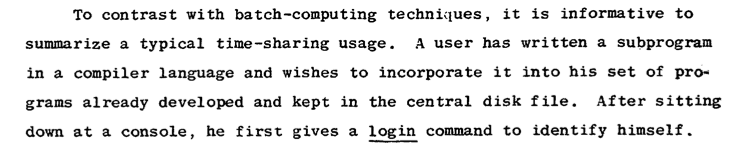

Representative terminal, not actually a CTSS terminal, CC LevitateMe

The OED’s earliest listed usage of “log in” in the modern sense of “to open one’s on-line access to a computer” is from the 1963 publication Compatible Time-Sharing System from the MIT Computation Center. [2] I’m not sure if this is truly the first usage of “log in”, but it would make sense if it was, as CTSS, started in 1961, was arguably the first time-sharing operating systems, and so possibly the first system that you needed to log in to. (Before that we only had batch processing systems).

Whether it was CTSS or a similar system, I envision an engineer, probably at MIT, somewhere between 1959 and 1961, needing to describe a new user command for the system they were creating.We get a lot of neologisms from these situations, and it’s very possible log in dates from just this moment in history.

CTSS Timeshare: A Programmer’s Guide, MIT press

It’s also possible that “log in” was used in a non-computer sense before time-share systems, but I haven’t seen it in print. But of course the “log” part, meaning to record something or someone, predates computers by hundreds of years.

Ship’s log CC David Churbuck

That usage is in turn a shortening from entering something into a “log-book”, or ship’s log, (or captain’s log, if you’re in Starfleet) which the OED defines as:

A book in which the particulars of a ship’s voyage (including her rate of progress as indicated by the log) are entered daily from the log-board.

The first listed usage of log-book or logbook is from roughly 1689 ( J. Moore’s New Syst. Math). By travelling back 250 years in time, we’ve gone from identifying ourselves within a computer system to entering the speed of a sailing ship into a book.

But why was it called a logbook? Because of this apparatus here, variously called a chip log, ship log, or log:

Chip log log line, & reel, CC Kate’s Photo Diary

A log! Or at least, a piece of heavy wood, attached to a knotted rope. Which you throw overboard and time how many knots go by for a set period of time, or, as Wikipedia describes it:

When the navigator wished to determine the speed of his vessel, a sailor dropped the log over the stern of the ship. The log would act as a drogue and remain roughly in place while the vessel moved away. The log-line was allowed to run out for a fixed period of time. The speed of the ship was indicated by the length of log-line passing over the stern during that time.

This is also why we still measure nautical speed in knots. So, when you next log in to Facebook or Gmail, think about big hunks of wood being thrown off the side of a ship to measure speed.

P.S. This was fun and entertaining for me to put together, but I’m sure there are holes and inaccuracies. If you know more about the origins of “log in”, please chime in with comments, and I’ll update accordingly!

Update 8/6/11: In a comment, Andrew Durdin points to some non-computer uses of “log in” from the 1950s. Awesome!

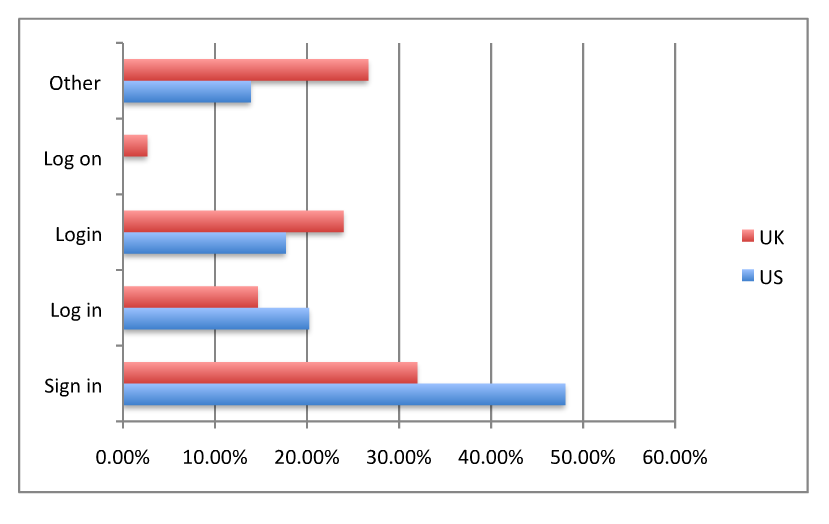

Note 1: A couple of years ago I did a survey of top websites in the US and UK and whether they used “sign in”, “log in”, “login”, “log on”, or some other variant. The answer at the time seemed to be that if you combined “log in” and “login”, it exceeded “sign in”, but not by much. I’ve also noticed that the trend toward “sign in” is increasing, especially with the most popular services. Facebook seems to be a “log in” hold-out.

If the whole “sign in” vs. log in” debate is interesting to you, there are some debates here and here. My personal feeling is that either is fine, but “sign in” is marginally more friendly and probably the preferred usage, though I’ll miss the nautical association. On the other hand, I feel strongly that “login” as a verb is an abomination and not to be tolerated under any circumstances.

If you’re really interested, you might start noticing where sites show their own evolutions and inconsistencies of usage. For example, Twitter’s web UI uses “sign in” but the URL says “login”. But now we’re probably reaching the outer limits of obsession and should stop.

Note 2. Here’s a PDF of a CTSS manual from 1964. There’s an underlined “log in” on page 6.

Interestingly, CTSS is also the system that gave us the first email system, as described by Errol Morris in his history of his brother’s role in the creation of that system. The Wikipedia history of CTSS is pretty fascinating stuff as well, and contains links to oral histories of the creation of CTSS and Multics (the precursor to Unix).